O Really wrote: ↑Fri Dec 06, 2024 12:30 pm

Vrede too wrote: ↑Fri Dec 06, 2024 11:14 am

Yup. The mistaken assumption here is that these laws and policies have ever been about treating addiction and problematic drug use. Instead, they're designed for systemic racism, gutting the Constitution and expanding the police/prison industrial complex. With these goals the Drug War has been enormously successful.

No, the laws were never about rehab, but saying they're designed for "...systemic racism..." etc. is like saying the original Prohibition was designed to benefit and enhance the profitability of gangsters. Creating a booming bootleg and related crime industry was an unintended (but predictable) consequence, not part of the plan. I don't really think they sat around and said "what can we do to make life more miserable on Black people and make more money off prisons? Oh yeah, let's criminalize addiction" More likely, IMNVHO, is that from a couple of centuries drunkenness was treated as a moral failing, not an illness. Continue that to drugs, and you've got punishment with no compassion.

https://drugpolicy.org/drug-war-history/

1870-1920

The First U.S. Anti-Drug Law Targeted Chinese Immigrant Communities ...

Anti-Cocaine Laws Targeted Southern Black People

... Experts testified that “most of the attacks upon white women of the South are the direct result of a cocaine-crazed Negro brain.”

First Federal Marijuana Law Targeted Mexican Immigrants

Harry Anslinger became the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. He claimed marijuana caused psychosis and violence. Only one of 30 scientists agreed. Anslinger shared a letter with Congress, “I wish I could show you what [marijuana] can do to […] degenerate Spanish-speaking residents.”...

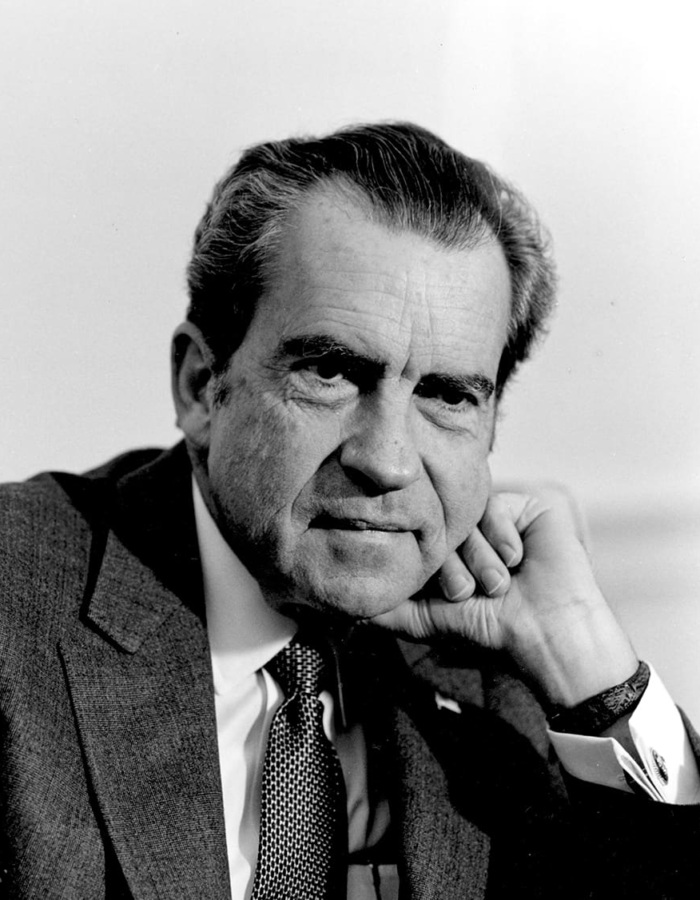

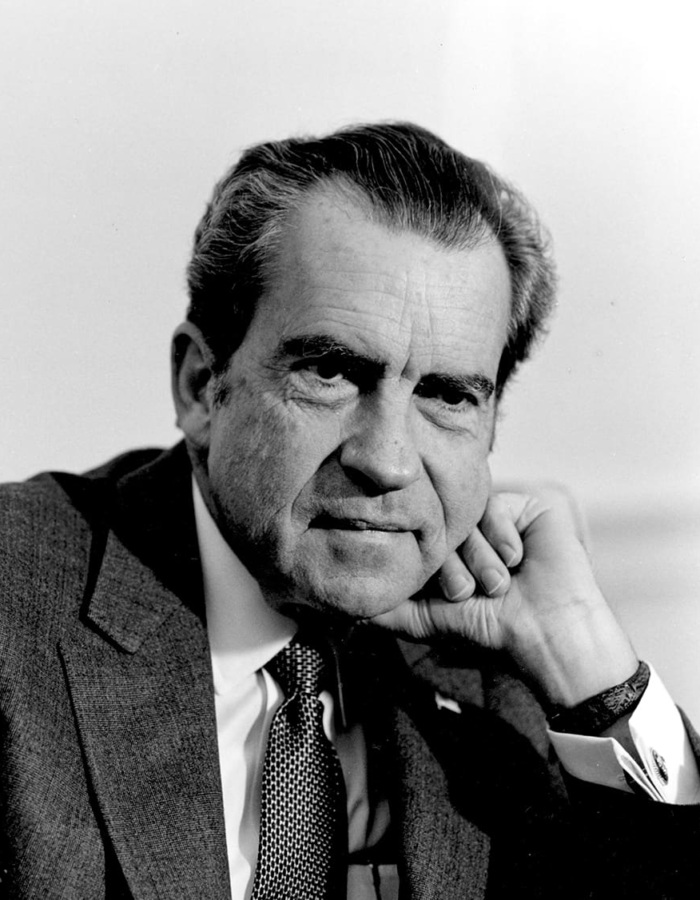

His Southern Strategy wasn't solely about getting White voters to switch to the GOP. It was also about deliberately decimating Black communities with drugs and drug law enforcement.

"unintended"?

Drug War Stats

Drug Arrests

Drug offenses are a leading cause of arrest in the U.S.

These arrests more often impact impact Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people and those with low-income....

Black people are 24% of those arrested due to targeted policing

Black people are 24% of those arrested, but only make up 13% of the U.S. population -- and people of all races use and sell drugs at similar rates. This arrest rate is instead due to targeted policing, surveillance, and punishment tactics.

Source:

FBI

...

3 Systemic Impact

...

Drug offenses were second most common cause of deportation

After illegal entry, drug offenses were the most common cause of deportation in 2019.

Source:

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse

6 Marijuana Policy

... Black people are 3.6 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana than white people nationally, despite similar rates of use. This disparity is even higher in many states.

Source:

ACLU

Report: “Disrupt and Vilify”: The War on Immigrants Inside the U.S. War on Drugs

Report

Factsheet

Marijuana-related factsheet

Search DPA: race and the drug war

"unintended"?

As for making "more money off prisons":

...

5 Financial Impact

$47 billion

is the estimated cost to enforce drug prohibition in the U.S. every year.

... Taxpayers spent $3.3 billion funding the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 2021. The agency costs $6,300 per minute to run.

Source:

Drug Enforcement Administration

$169 million worth of military equipment to fight drug war in 2022

$169 million worth of military equipment was transferred to law enforcement through the 1033 program in 2022. This program militarizes police with armored vehicles, body armor, and rifles to monitor and punish drug use, sales, and activity.

Source:

Defense Logistics Agency

If you think that this doesn't create a massive constituency invested in continuing and expanding Drug War spending, you are very naive about the impact of money. Police/Prison Industrial Complex is not hyperbole, it's fact.

Wiki: Prison–industrial complex

The

prison-industrial complex (PIC) is a term, coined after the "military-industrial complex" of the 1950s, used by scholars and activists to describe the many relationships between institutions of imprisonment (such as prisons, jails, detention facilities, and psychiatric hospitals) and the various businesses that benefit from them.

The term is most often used in the context of the contemporary United States, where the expansion of the U.S. inmate population has resulted in economic profit and political influence for private prisons and other companies that supply goods and services to government prison agencies. According to this concept, incarceration not only upholds the justice system, but also subsidizes construction companies, companies that operate prison food services and medical facilities, surveillance and corrections technology vendors, corporations that contract cheap prison labor, correctional officers unions, private probation companies, criminal lawyers, and the lobby groups that represent them. The term also refers more generally to interest groups who, in their interactions with the prison system, prioritize financial gain over rehabilitating criminals.

Proponents of this concept, including civil rights organizations such as the Rutherford Institute and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), believe that the economic incentives of prison construction, prison privatization, prison labor, and prison service contracts have transformed incarceration into an industry capable of growth, and have contributed to mass incarceration. These advocacy groups note that incarceration affects people of color at disproportionately high rates....

The War on Drugs

Marc Mauer, executive director of the criminal justice reform group The Sentencing Project, has argued that the growth and expansion of the prison-industrial complex since the 1970s has its roots in the War on Drugs, which, rather than suppressing the illegal drug trade, has produced a perpetual cycle of drug dealing and imprisonment. This he attributes to a structural feature of the drug trade, a market with perpetually high demand and lucrative potential profits. Mauer describes the "replacement effect", in which no matter how many drug suppliers are incarcerated, other sellers simply take their place; since there is a constant supply of new drug sellers, there is thus a constant supply of potential prison inmates. According to this view, the prison-industrial complex depends on this guarantee of future inmates to ensure its growth and profitability, making prison construction, operation, services, and technology all safe investments.

Professor Angela Davis, one of the most recognized American prison abolition activists, has argued that while some appear to believe that the prison industrial complex is taking the space once filled by the military industrial complex, the aftermath of the War on Terror shows how the links between the military, corporations, and government are growing even stronger. The relationship between these complexes, Davis suggests, shows they are symbiotic, because they mutually support and promote each other, even sharing some technologies. Further, they also share important structural features, both generating immense profits from processes of "social destruction" In essence, Davis argues that the relationship between the military and prison industrial complex can be understood like this: the exact things which are advantageous to corporations, elected officials, and governmental agents, those who have evident stakes in expanding these systems, leads to the devastation of poor and racialized communities as it has throughout American history.

Aside: What an unexpected treat it is to have reason to cite Professor Angela Davis.

Now the ACLU:

A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

Race and Criminal Justice ...

FAQ

1. What is the War on Drugs?

President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs” in 1971. By the 1980s, the link between minorities, drugs, and crime was firmly cemented in American rhetoric. Media hysteria about an unsubstantiated crack epidemic among Black communities prompted Congress to pass draconian mandatory minimum sentencing laws against crack cocaine. The war on drugs has sent millions of people to prison for low-level offenses, and seriously eroded our civil liberties and civil rights while costing taxpayers billions of dollars a year, with nothing to show for it except our status as the world’s largest incarcerator.

2. Is there institutional racism in marijuana arrests?

On average, a Black person is 3.64 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than a white person, even though Black and white people use marijuana at similar rates. In every state, and in over 96 percent of the counties examined in our 2020 analysis, Black people were

much more likely to be arrested than white people for marijuana possession. Overall, these disparities have not improved. In 10 states, Black people were more than five times more likely to be arrested.

3. How is police violence a form of institutional racism?

Police violence stems from this country’s history of using police to oppress marginalized people. American policing has never been a neutral institution. It perpetuates racism and oppression by design. From “slave patrols” that used terror and torture against enslaved Black people engaged in uprisings, to armed militia that enforced Black Codes and Jim Crow, to police that subverted labor unions to benefit political elites in the 19th century, policing has always been tied to suppression, surveillance, and control.

What's at Stake

There are significant racial disparities in sentencing decisions in the United States. Sentences imposed on Black males in the federal system are nearly

20 percent longer than those imposed on white males convicted of similar crimes. Black and Latine defendants sentenced in state and federal courts face significantly greater odds of incarceration than similarly situated white defendants and receive longer sentences than their white counterparts in some jurisdictions.

These racial disparities are not unintentional. From the beginning, the war on drugs has decimated the Black community and communities of color, a result of sentencing disparities and selective enforcement of drug laws. Today, there are more Black people under the control of prison and corrections departments than were ever enslaved by this country.

These racial disparities result from disparate treatment of Black and Brown people at every stage of the criminal legal system, including stops and searches, arrests, prosecutions and plea negotiations, trials, sentencing, parole, and probation revocation decisions. Race matters at all phases and aspects of the criminal process, including the quality of representation, the charging phase, and the availability of plea agreements.

Race & the War on Drugs